The name “Circus Maximus” still echoes with a sense of epic scale, so much so that modern entertainers borrow its grandeur. The recent Circus Maximus Tour by Travis Scott not only became the highest-grossing solo rap tour in history but also drew crowds of over 125,000 in a single stop, a testament to the enduring power of the name Live Nation, 2025. Yet, the ancient reality behind that name dwarfs any modern concert. Imagine a venue not for thousands, but for hundreds of thousands, where the roar of the crowd was a physical force, and the dust kicked up by thundering hooves was the very breath of ancient Rome. This was the Circus Maximus, the largest and oldest stadium in the Roman Empire, a place where spectacle, politics, and raw human emotion collided in a breathtaking display.

An Enduring Icon of Roman Power and Entertainment

More than just a racetrack, the Circus Maximus was the beating heart of Roman public life for over a millennium. As the premier stage for the Ludi Romani, the Roman Games, it was the epicenter of a culture that perfected mass Roman entertainment. The arena was immense and enjoyed a very long history. Its scale showcased Rome’s unparalleled engineering skill and imperial wealth. Furthermore, its ability to entertain a huge number of citizens demonstrated Rome’s commitment to public spectacle on a scale previously unimaginable.

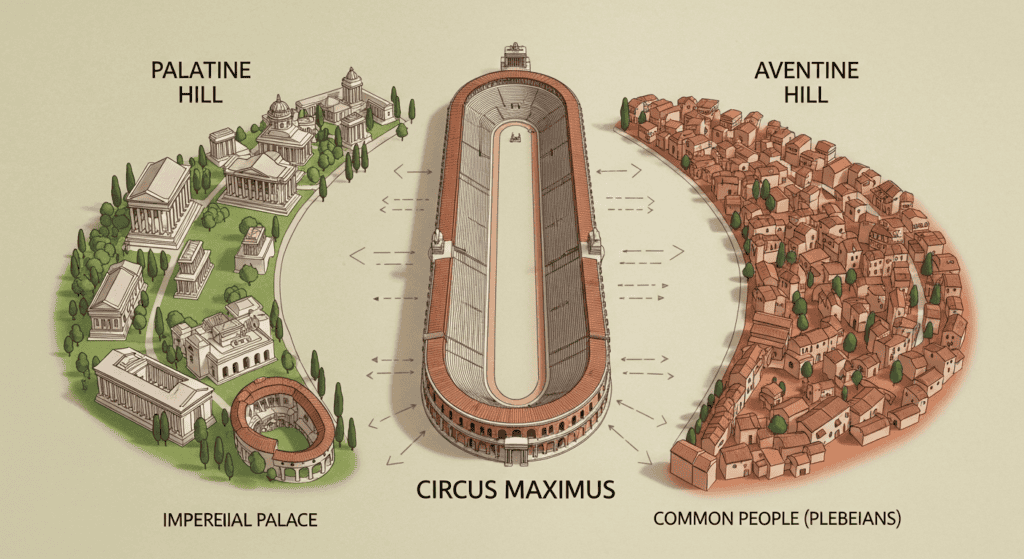

The Circus Maximus was strategically placed between the Palatine Hill (home to emperors) and the Aventine Hill (home to the common people), making it a central stage for all of Roman society.

The Circus Maximus was strategically positioned in the valley between the prestigious Palatine Hill and the populist Aventine Hill. The Palatine was the home of emperors, while the Aventine was associated with the common people. This placement in the city’s center was both strategic and symbolic. Its location made it accessible to all strata of society, a crucial element for emperors seeking to provide “panem et circenses” (bread and circuses) to maintain public favor. The events held here were not mere distractions; they were a fundamental part of Roman civic and religious life.

Beyond the Stones: Unveiling Rome’s Epic Arena

Today, the site is a vast public park, its stone seating long since plundered for other buildings. But beneath the grassy expanse lie the foundations and the story of an arena without parallel. To truly grasp its significance, we must look beyond the ruins. We need to uncover the astonishing facts about this epic arena, from its colossal capacity to the life-and-death drama that unfolded on its sands.

Astonishing Fact 1: A Colossus of Capacity – Rome’s Gigantic Entertainment Hub

The most immediate and staggering fact about the Circus Maximus is its sheer size. It was not merely a large stadium; it was an architectural titan that dwarfed any other structure in the ancient world and continues to challenge modern equivalents. Its scale was a direct reflection of Rome’s ambition and its need to manage and entertain a colossal urban population. The estimated capacity of the Circus Maximus dwarfs even the largest modern stadiums, showcasing the immense scale of Roman public entertainment.

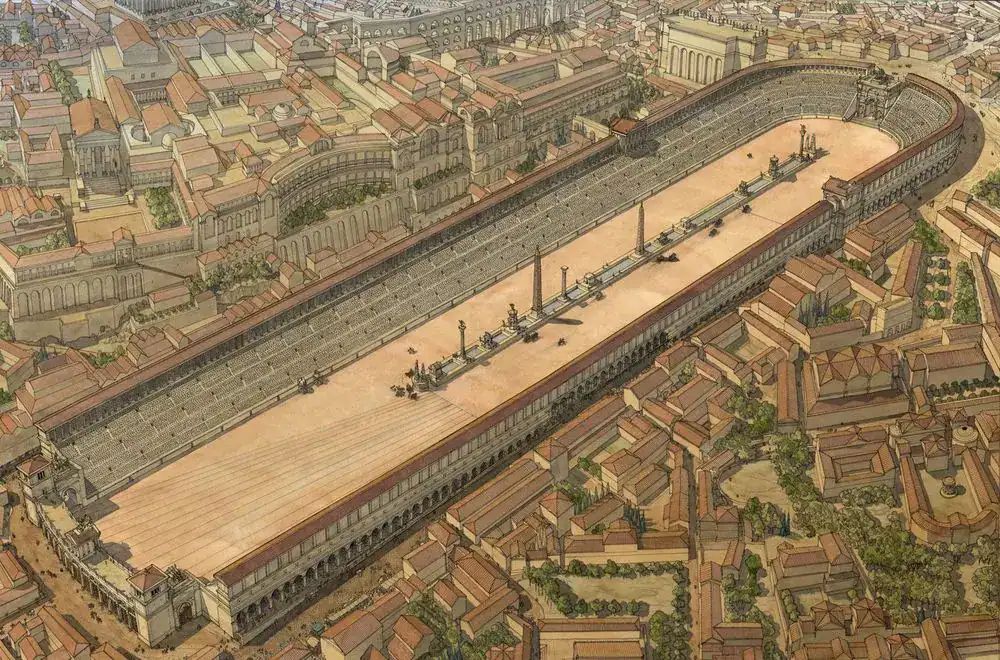

More Than Just Big: Drowning Modern Stadiums in Scale

Modern mega-stadiums, which typically hold around 80,000 to 100,000 spectators, would be lost within the footprint of the Circus Maximus. Historical sources, such as the writings of Dionysius of Halicarnassus, and archaeological estimates suggest the Circus could accommodate between 150,000 and 250,000 people. At its peak, this meant that a significant portion of Rome’s population could attend an event simultaneously. The structure itself was immense, measuring approximately 621 meters (2,037 ft) in length and 118 meters (387 ft) in width.

Strategic Location: Nestled Between Palatine and Aventine Hills

The choice of location in the Murcia Valley between the Palatine Hill and Aventine hill was no accident. This long, flat area was naturally suited for a racetrack. The stadium’s proximity to the Palatine, where emperors resided, established a direct and almost theatrical connection between the ruling class and the masses. From the imperial box, the emperor had a commanding view of both the races and the sprawling crowd.

The Sheer Numbers: An Unfathomable Crowd for the Ancient World

To comprehend the scale, one must imagine the logistics of moving, seating, and controlling a quarter of a million people without modern technology. The roar of a crowd that size would have been deafening, a constant wave of sound washing over the city. This massive audience was a spectacle in itself, a living testament to the power of Rome to gather its people for shared, visceral experiences that reinforced a collective identity.

An Architectural Marvel: Early Origins and Continuous Expansion

According to Roman historians like Livy, the story of the Circus begins during the Roman Republic with Rome’s fifth king, Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, who first laid out the track and built rudimentary wooden seating. Over centuries, it evolved dramatically. Julius Caesar undertook a major expansion of the arena. After a devastating fire, Emperor Augustus rebuilt it with stone and famously added the first Egyptian obelisk to its central barrier. Later, Emperor Trajan would oversee its final and most magnificent form, a marble-clad wonder of Roman engineering.

Astonishing Fact 2: The Thrill and Terror of Chariot Racing – A Dance with Death

While the Circus Maximus hosted various events, its soul belonged to the chariot races. This was not a sport in the modern sense; it was a high-stakes, violent, and wildly popular obsession that gripped Roman society. The races were a potent mix of athletic skill, raw courage, and mortal danger, making them the premier form of Roman entertainment.

The Main Event: Heart-Pounding Races and Brutal Crashes

The standard race consisted of seven frantic laps around the central barrier, known as the spina. Chariots, often pulled by four horses (a quadriga), reached incredible speeds on the long straights. The most dangerous points were the tight, 180-degree turns around the conical turning posts, or metae, at each end of the spina. Collisions here were frequent and brutal, a chaotic tangle of splintering wood, flailing horses, and broken men often referred to as a naufragia, or “shipwreck.”

The Factions: Fierce Loyalty and Riotous Rivalry (Reds, Whites, Blues, Greens)

Charioteers didn’t race for themselves but for one of four professional factions: the Reds (Russata), Whites (Albata), Blues (Veneta), and Greens (Prasina). These factions operated like modern sports franchises, with stables, trainers, and vast financial backing. Fans displayed a fanatical loyalty, wearing their faction’s colors and betting heavily on the outcomes. Rivalries were so intense that they often spilled out of the Circus and into the streets as violent riots.

Charioteers as Superstars: Wealth, Fame, and the Gaianus Apuleius Diocles Legend

Successful charioteers were the superstars of their day, earning adoration and immense fortunes. The most renowned charioteer was Gaius Apuleius Diocles, who raced in the 2nd century AD. His career winnings reportedly amounted to 35,863,120 sesterces—an astronomical sum that could have paid the annual salary for the entire Roman army at the time. His fame and wealth illustrate the incredible cultural status afforded to these death-defying athletes.

The Mechanics of the Race: Starting Gates, Spina, and Metae

The spectacle began with immense tension at the carceres, or starting gates. A complex spring-loaded mechanism ensured a fair start for all twelve chariots. Once released, they thundered down the track, jockeying for position before the first turn around the metae. The long central spina was the track’s defining feature, an ornate barrier decorated with statues, fountains, and other monuments to the gods and emperors.

Astonishing Fact 3: More Than Just Races – A Canvas for Diverse Public Games

Chariot racing may have been the main attraction, but the versatility of the Circus Maximus allowed it to be a stage for a wide array of public games and imperial celebrations. Its vast space could be adapted for events that were by turns celebratory, athletic, and horrifyingly brutal, making it a truly multi-purpose venue.

The Gruesome Spectacle of Venationes: Animal Hunts and Exotic Beasts

The arena frequently hosted venationes, or animal hunts. For these events, the Romans imported exotic and dangerous creatures from across the empire—lions, tigers, elephants, bears, and crocodiles. These hunts were often large-scale slaughters designed to showcase Rome’s dominion over the natural world. Pompey the Great once staged a hunt involving hundreds of lions and leopards, and Emperor Probus famously had the arena filled with trees to simulate a forest for a massive hunt.

Athletic Contests and Foot Races: Showcasing Roman Strength and Skill

In its earlier history and during specific festivals, the Circus was also used for athletic contests. These included foot races, wrestling, and boxing, events that harkened back to the ancient Greek Olympics but were given a distinctly Roman flavor. These contests celebrated physical prowess and military conditioning, core values of Roman society. While less common than at the Colosseum, historical records suggest that occasional gladiator fights or combat displays also took place here, particularly as part of larger triumphal games.

Grand Triumphs and Military Displays: Celebrating Imperial Power

The Circus Maximus was the endpoint for the Roman Triumph, the highest honor a victorious general could receive. A triumphal procession would parade through the city, culminating in a grand display at the Circus, where the general would showcase the spoils of war and prisoners to the adoring masses. The arena also hosted mock battles and large-scale military parades, reinforcing the might of the Roman legions.

From Mock Battles to Religious Rites: The Multifaceted Roman Games

The events held in the Circus were part of the Ludi Romani, or Roman Games, which were fundamentally religious festivals. Therefore, even the most violent spectacles were framed within a sacred context. Processions honoring deities like Jupiter would precede the games, directly linking entertainment with religious duties. This multifaceted role made the Circus a central pillar of Roman cultural and spiritual life.

Astonishing Fact 4: Gods, Goddesses, and the Sacred Ground of the Circus

Beneath the thundering hooves and roaring crowds, the Circus Maximus was fundamentally sacred ground. Its origins were steeped in mythology and religious cults, and the very ground it was built upon was believed to be watched over by ancient deities. This religious dimension is often overlooked but was essential to the arena’s significance and its role in Roman life.

Dedication to Consus: The Hidden God of the Circus

The valley was originally home to an underground altar dedicated to Consus, an ancient Roman god of grain and storage. His altar was buried and ceremonially uncovered only during specific games held at the Circus. This ritual symbolically connected the agricultural bounty of the land with the public games held upon it, suggesting the Circus’s deep roots in Rome’s archaic, agricultural past.

The Deity of the Valley: Murcia and Her Ancient Presence

The valley itself was known as the Vallis Murcia, named after an obscure early deity, Murcia. She was associated with the myrtle tree and Venus, the goddess of love. A shrine to her stood within the Circus, integrating another layer of divine presence into the site of spectacle and competition. Its proximity to the Forum Boarium, an ancient cattle market with its own powerful cults like the Hercules Ara Maxima, further cemented the area’s religious importance.

Imperial Cults and Other Gods: A Pantheon of Spectators

The arena was not just for mortal spectators. A temple to the sun god Sol and the moon goddess Luna overlooked the eastern end, and the emperors themselves, often deified, had a prominent box (pulvinar) that resembled a temple platform. The entire Circus was filled with statues and shrines, creating an environment where gods and men watched the games together. Emperor Nero even participated in races, an act that blurred the line between the divine ruler and mortal entertainer.

The Religious Significance of the Roman Games

The public games were not secular entertainment. They were religious observances, held on holy days to honor the gods and secure their favor for Rome. The races, the triumphs, and even the hunts were rituals performed on a massive scale, reinforcing the pact between the Roman state and its divine patrons.

Astonishing Fact 5: Engineering Marvels and Imperial Ambition

The final form of the Circus Maximus under Emperor Trajan was a masterpiece of Roman engineering. Its construction, upkeep, and the complex systems required for events reveal an incredible level of sophistication. Building and maintaining the arena was a complex task. The operation of the events required advanced systems, and this high level of skill and planning was driven by imperial ambition.

From Wooden Stands to Stone Grandeur: Evolution of the Structure

The early Circus was largely a wooden structure, making it highly susceptible to fire. After several destructive blazes, emperors like Augustus and later Trajan invested heavily in rebuilding it with stone and marble. The tiered seating rested on a complex series of concrete vaults and arches, which housed shops, food stalls, and betting dens, creating a vibrant ecosystem around the arena.

Key Features of the Arena: The Spina, Metae, and Obelisks

The spina, the central barrier, was the arena’s decorative and functional heart. It was not just a wall but a long, ornate platform over 300 meters long, adorned with statues, fountains, and spoils of war. At each end stood the conical turning posts, the metae, which defined the perilous turns of the race.

The Obelisks of Egypt: Imperial Trophies Adorning the Spina

To demonstrate Rome’s power, emperors decorated the spina with trophies from conquered lands. The most magnificent of these were two massive Egyptian obelisks. Augustus erected the first one, the Obelisco Flaminio, which now stands in the Piazza del Popolo in Rome. Centuries later, Constantius II added an even larger one, now located near the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran. These ancient monuments served as powerful symbols of Rome’s dominion over the known world.

Ingenious Scoring Systems: Dolphins and Eggs to Mark the Laps

Keeping track of the seven laps amidst the chaos of a race was crucial. The Romans developed an ingenious public scoring system on the spina. It featured two sets of seven large, carved markers—one of egg-shaped objects and another of bronze dolphins. After each lap, an official would turn one egg and one dolphin to indicate the lap count to the charioteers and the tens of thousands of betting spectators. The choice of eggs honored Castor and Pollux, patrons of horses, while the dolphins honored Neptune, the god of horses and the sea.

Conclusion

The Circus Maximus was far more than ancient Rome’s epic arena; it was a microcosm of the empire itself. The skill of Roman engineers was remarkable. They had a great love for large-scale spectacles. Religion was deeply intertwined with public life, and emperors wielded immense power to capture the attention of the vast populace. Its legacy persisted even after the fall of Rome. Other Roman circuses, like the well-preserved Circus of Maxentius on the Appian Way, continued the tradition, but none ever matched the scale of the original.

After its last race in 549 AD, the great arena fell into disuse. Its stones were quarried for new buildings, and over centuries, the valley filled with earth. It was Pope Sixtus V in the 16th century who began its modern transformation, moving the Egyptian obelisks to their current locations.

Today, as visitors walk the vast grassy track, the echo of thundering chariots remains. While the marble stands are gone, the sheer scale of the space continues to inspire awe. Modern visitors can even get a glimpse of its former glory through the “Circo Maximo Experience,” an immersive tour using virtual and augmented reality to resurrect this astonishing monument from the dust of ages. The significance of the Circus Maximus in Ancient Rome cannot be overstated; it was the ultimate stage for the empire’s power, passion, and piety.